Editor, Webmaster: Phil Cartwright Editor@earlyjas.org

|

| Earlville Association for Ragtime Lovers Yearning for Jazz Advancement and Socialization |

EARLYJAS

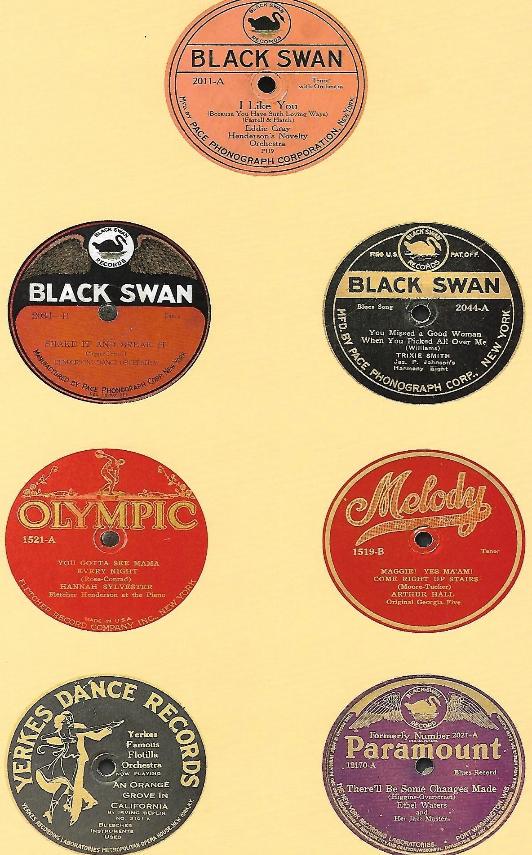

Black Swan Records and the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem area of New York City became the center of a growing black population, based on the

migration of southern blacks due to harsh southern Jim Crow laws, and the need for workers during WWI.

Already a cultural center, New York’s atmosphere and opportunities led to what is now known as The

Harlem Renaissance, an intellectual flowering. Black art, literature and music flourished – and jazz began

to enter the scene. Of special note were two events and a happening. In 1912, James Reese Europe’s Clef

Club Orchestra gave a concert in Carnegie Hall which was well received. In 1921 Eubie Blake and Noble

Sissle opened “Shuffle Along,” an all-black musical with jazz overtones, very popular with all theater-

goers; it ran for 504 performances, a great success for its time and composition. The happening: James P.

Johnson had synthesized emerging piano styles into what became known as Harlem stride piano; his first

recording, “The Harlem Strut,” was on Black Swan. Financially, more blacks were doing well and a new

market was opening for what became known as “race records.” In 1920, Okeh released “Crazy Blues” by

Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds, with Willie “The Lion” Smith on piano. It sold over 250,00 copies,

50,000 in Harlem alone!

Enter Harry Pace of Pace & Handy, music publishers from Memphis, now in New York City. William

C. Handy was writing music and touring with a brass band; Pace joined him in 1905 as the financial

manger of the team. They remained as an obscure and struggling team until 1914, with the release of “St.

Louis Blues.” The song was a resounding success, and they added more successes to their credit, such as

“Yellow Dog Blues,” “Memphis Blues” and “Careless Love.” In that period, sheet music sales, not

records, were the driver in the music business, and in 1918, they moved to New York City to be closer to

the action.

Originally the record business was controlled by two companies, Victor and Columbia, Between them

they held patents which precluded any “upstarts” from getting into the business. However, one upstart,

Gennett Records, challenged Victor in court - and won, opening up opportunities for small labels to enter

what was now a growing market for jazz and blues. Gennett did well, recording such musicians as Jelly

Roll Morton, King Oliver and Louis Armstrong. Pace saw an opportunity, left Handy and formed the Pace

Phonograph Co, in 1921, with Fletcher Henderson as musical director. However, Pace did not press; he

had to farm out that process. His new presser was The Wisconsin Chair Co. which owned two labels,

Puritan and Paramount. Pace was now ready to release records by “The only phonograph company

owned and controlled by colored people.” Furthermore, he advertised that Black Swan records were “The

only records using exclusively Negro voices and musicians.”

Harry Pace, Jr.

While Pace had a good sense of opportunity, his recognition of market demand was not.

His new label was named Black Swan, in honor of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield, a noted 19th

century black concert singer. And he wanted Black Swan to offer a variety of music, much

of it (in his opinion) culturally uplifting. His first three releases were a concert singer, a

hymnist and vaudeville singer Katie Crippen doing “Blind Man Blues.” This was post-war

America; tastes had changed. Not hard to figure out which record of the three sold. Pace

had a stroke of good luck in securing Ethel Waters under exclusive contract. Her first

recording, “Down Home Blues,” was a success. Pace also added Albert Hunter and Trixie

Smith to his recording roster. Sales were up, he made a good profit in 1921, and purchased

a defunct recording studio in April of 1922. Now he could press his own records and keep

up with demand.

1922 went well for Pace, and 1923 was off to a good start but there were changes in the

industry that would affect him. The race record market was doing well, and some of his

competitors were pursuing it aggressively, responding to demand for blues from the

southern U.S. Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith were popular, and the accompanists were not

pit orchestra types as used by Black Swan, but major players in the new jazz idiom such as

Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet and Clarence Williams. And another competitor to records

themselves appeared – radio. Pace lost some of his stars to competition, while the demand

for records dropped as the number of producers increased. Bad news for Black Swan.

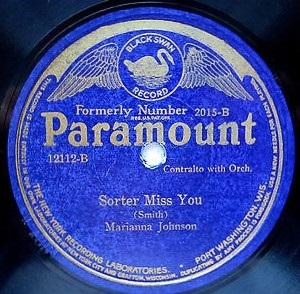

By the end of 1923, Pace’s luck had run out; in 1924 he leased his masters to Paramount,

which re-issued 90 of them on a Paramount label with a Black Swan insert. Harry Pace left

the music business, returning to the insurance industry where he had started. He retired as

a successful business man and died in 1943. His place in jazz history is secure as the

founder and operator of America’s first Afro-American record label.