Editor, Webmaster: Phil Cartwright

Editor@earlyjas.org

Editor@earlyjas.org

|

| Earlville Association for Ragtime Lovers Yearning for Jazz Advancement and Socialization |

EARLYJAS

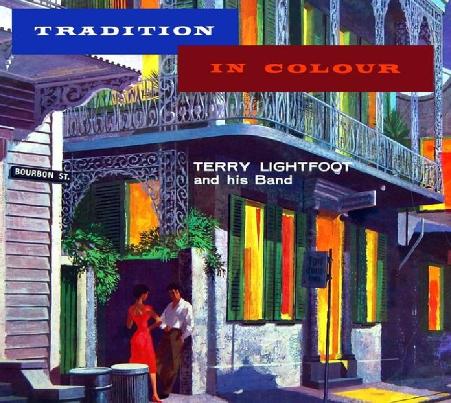

The British Trad Jazz movement of the 1950s and ‘60s, when acknowledged by

jazz historians at all, is generally footnoted among the various revivals of early

New Orleans style, beginning with Bechet’s Blue Note recordings and the various

renewals of interest driven by Louis Armstrong’s extended career. While there is

certainly truth to this categorization, such a pigeon hole can also be misleading and

devaluing when we really consider the achievement of the actual music: “Creative

Resurgence” would be my choice as a better way of understanding what actually

happened. Of the many masterful, and deceptively innovative, albums to be

released in a very short period of time, Terry Lightfoot’s Tradition in Colour

remains a strong example.

The title of each tune makes a nod to the visible spectrum, and leading off with

“Green for Danger” we’re thrown right into the Trad Jazz aesthetic—more modal

and streamlined than most revival jazz, Wayne Chandler’s banjo standing out more

prominently as an organizational influence, the drums (played by a young Ginger

Baker) taking a less dominant, more timbral role. Lightfoot’s clarinet, from

beginning to end of the album, is excellent—rich, powerful in all registers, layered,

Edmond Hall seem evident, but any and all role models have been fully integrated

into a new voice in the jazz clarinet world—confident, relaxed, commanding

without being overbearing, ruminative (especially on his salute to George Lewis in

“Burgundy Street Blues”).

While Lightfoot is the focus, taking the spotlight on the majority of solo numbers,

he gives Colin Smith a chance to show off his strong trumpet in Fats Waller’s

“Blue Turning Grey Over You.” Later in the album, he features John Bennett’s

trombone on “My Blue Heaven.” Bennett in particular seems to have a sound

indebted to the English Brass Band tradition, unique in wind playing for its mellow,

round, shimmering quality. This is one of the great treats of British Trad Jazz, by

the way: the British brass tradition is less buzzy and directional than many others,

and the warmth that they bring can change the repertoire immediately, offering

different angles on each tune.

Terry Lightfoot himself, however, must be singled out for high praise. His soloing

style, while owing a debt to American forefathers, is likewise a product of a

specifically British style of clarinetistry, fused to the New Orleans tradition. The

richness of his chalumeau, which seamlessly glides into the clarion register, is

unique. He is less impetuous and more methodical in his soloing ideas, opting to

use motivic cells throughout distinct choruses. That type of playing, more

emotionally circumspect, would seem to be antithetical to blues playing, but in

Lightfoot’s case it is not: He impresses by being ruminative and contemplative

rather than disengaged or cerebral. His blues are deep and strong, even in their

detached quality. Most gratifying is that he managed to play the full rich New

Orleans style chalumeau without falling into the trap of so many revival

clarinetists—going flat. Lightfoot’s execution of the music and the clarinet itself are

therefore of importance.

Unfortunately, “Orange Blossom”, is attributed to Lightfoot himself (at least on the

edition of the album I own), yet is unmistakably a George Lewis original, “St.

Philip Street Breakdown.” Unless this is a misprint, it can only be considered

embarrassing that the attribution was not acknowledged, marring an otherwise

fascinating album.

Terry Lightfoot and His Band: Tradition in Colour,

EMI (Encore! ENC 124), 1958